Back in 1988, a video collection under the title of “Mike Tyson Presents..” was released. I purchased the one titled “Boxing’s greatest knockouts”. Divided in to sections, the one that caught my attention was “Brutal knockouts”. It was here that I discovered one of boxing’s hardest punchers and one of the lightweight’s greatest ever champions, Isiah “Ike” Williams.

It was 12th July 1948 and Williams was defending his title against Philadelphia’s Beau Jack. This was the first of four meetings between the men. Jack, in his high pressure style, had let it all go in the first three rounds, as he had struggled with weight beforehand. But his aggression had played in to the heavy hands of the champion. Williams had the classic boxer’s physique: slender legs and torso with powerfully built arms and shoulders. And he carried knockout power in both hands, particularly his right. It was that shot that was the undoing of Jack. Stunned early in the sixth, he was knocked back to the ropes as Williams unleashed a truly vicious barrage of punches. As punch after punch thudded in to the unprotected jaw of Jack, driving him in to a corner, Williams turned to the referee, looking for the third man to stop what had become a one sided beating. The referee did indeed intervene, even though the hard as nails Jack would have continued. But this mixture of ferocity and compassion had me hooked on Williams. And his story was certainly that of a man who vehemently followed his own beliefs.

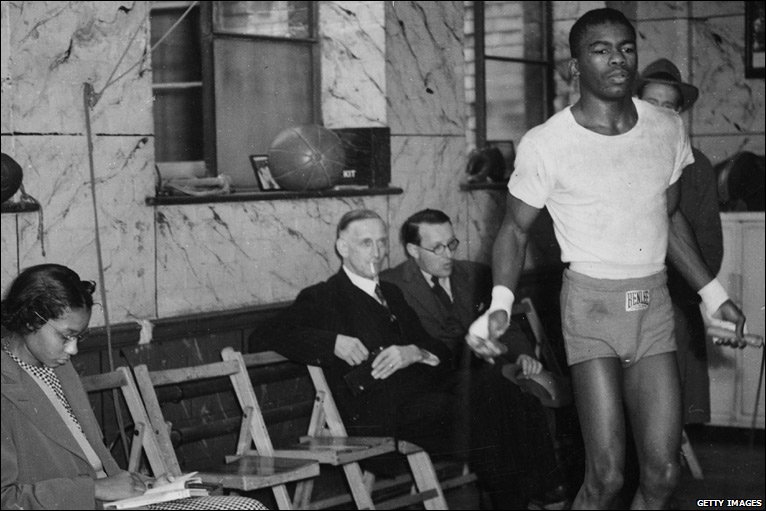

Born on 2nd August 1923 in Brunswick, Georgia, not too much is known about Williams younger years. He was, by accounts, a quiet and reserved child, possibly due to a slight speech impediment, but someone who excelled at sports. He took up boxing and won the Trenton Times Golden Gloves championship at featherweight aged just fifteen, before turning professional two years later in 1940.

Matched tough, as fighters were in those days, Williams second opponent Leroy Born had a record of 31-61-13, he lost to Billy Hildebrand in only his fourth fight. But losses weren’t viewed like they are today. Back then, they were part of a fighters learning curve and Williams avenged the loss in his very next fight, stopping Hildebrand in six. He lost a further three fights, and drew one with one no decision in his first sixteen fights, all against more experienced opponents, before going on a run of thirty four straight wins between November 1941 and December 1943, also reversing an earlier defeat to Tony Maglione, knocking him out in three. Former lightweight champion Bob Montgomery was the man who put an end to that, knocking Williams out for the first time in his career with a twelth round win. Williams, however, bounced back with fifteen straight wins. It was his two wins over former lightweight champion Sammy Angott though, that got the boxing world to take notice. Williams cleaner, sharper punching were in evidence against the mauling Angott, and he was becoming noticed for his smooth, crisp punching style. But every fighter has his boogeyman. And for Williams, slick boxing Willie Joyce was that man. They fought three times in Williams next seven contests, with Joyce taking a split decision in their first fight. Williams outpointed him in a rematch, then Joyce returned the favour in their third meeting. The speedster style of Joyce seemed to be the antithesis of Williams smooth, accurate punching but against many other great fighters of that era, Williams displayed his versatility, overcoming all styles.

In 1945, Williams landed his opportunity. A shot at the NBA title against champion Juan Zurita was set up in Zurita’s home country of Mexico. Zurita had a very impressive record of 130-22-1 and, according to reports, had been boxing professionally since the age of ten. However, this was Williams chance and he took it with both hands, ripping the title away with a second round stoppage. Non title fights were commonplace at this time and Williams went on a spree of these, besting some of the best fighters at lightweight and welterweight throughout his career, as outside issues prevented him from defending his title.

Connie McCarthy, Williams manager, was a round the clock alcoholic, and Williams parted company with him to try and take better care of his own career. But, in 1946, this sort of decision wasn’t acceptable from a fighter and Williams was blackballed by the Manager’s Guild and faced being banned from boxing. But the man who unofficially ran boxing was the notorious mafia Godfather Frankie Carbo, or “Mr. Gray”, as he was also known. He signed Williams over to one of his “associates”, Frank “Blinky” Palermo, a ruthless sort who gained the name Blinky as he was unable to hold eye contact with people for long, although this didn’t deter him from using unsavory way’s when dealing with certain “individuals”. Palermo assured him he would sort out the situation with McCarthy, take over his career and get Williams the fights and purses he should have as one of boxing’s finest champions.

For a period it seemed like Williams career was back on track. In his non title fights he had fought as high as 144 lbs, although he would fight as high as 155 lbs later on, and there is no question at all that in today’s world he would have been a three or four weight champion. He lost twice in this period, once by split decision to old rival Joyce and Sammy Angott also avenged both of his earlier defeat’s, stopping Williams in six. But Williams went on a streak, winning six of his next eight, with two draws, including victories over such fighters as Charley Smith, Johnny Bratton and Eddie Giosa, before making his first defence against Enrique Bolanos, stopping his tough foe in eight. For his second defence, he ventured overseas to Cardiff, facing the experienced Ronnie James who had lost just fourteen of one hundred and thirty one fights. Williams had too much for James, flooring him seven times in total, scoring a ninth round knockout. Six non title fights, five wins, followed before he met former conqueror Bob Montgomery for universal recognition as world champion. Montgomery held New York State recognition as lightweight champion.

This time though, Montgomery was no match for Williams. He was knocked down in the sixth before being rescued by the referee as Williams opened up, leaving Montgomery helpless. Eight non title fights followed, contested between the lightweight and welterweight divisions, against quality opposition. But the victory that stood out was the one over “The Cuban Hawk”, Kid Gavilan. Gavilan entered the ring with a record of 42-2-2 and was being primed for big things. But Williams had too much for him and took a unanimous decision. Defences of his title against Bolanos (Wpts 15), the aforementioned sixth round stoppage of Beau Jack, and a tenth round stoppage of Jesse Flores, saw Williams named both The Ring Magazine and The Boxing Writers Association of America fighter of the year for 1948.

Williams was matched again with Kid Gavilan. While he had soundly beaten Gavilan before, this time he was told to lose by Palermo. The mob had a big interest in Gavilan and believed he was headed for bigger things.

For his acceptance he would be “rewarded” $100,000. Williams refused and Gavilan took a close decision that most, including ringside observer Sugar Ray Robinson, thought Williams had more than won. This was the other side of the coin when being managed by Palermo and the mob. Even though Williams was active, he hardly saw any of the money he had made. But the one thing they couldn’t take was his pride and fighting heart. He dropped another decision to Gavilan, conceding nearly ten pounds in weight, and then, after two wins, he defended his title against old foe Bolanos. Again, another mobster, West Coast’s Mickey Cohen offered him money to throw the fight. Williams flat out refused. On 21st July 1949, with Jack Dempsey as referee, and Hollywood stars gathered ringside, Williams produced his finest performance, knocking out Bolanos in four. That he could recall that night and every punch years later tells you how much it meant to him. He made his last successful defence five fights later against Freddie Dawson, in another fight he was supposed to throw and another one he refused, winning a unanimous fifteen round decision. He campaigned mainly at welterweight, taking on the best contenders the division could offer, Johnny Bratton, Sonny Boy West and Lester Felton being amongst his victims. He swapped a pair of decision’s with Charley Salas and was bested two out of three times by Joe Miceli. Rudy Cruz was outpointed before Jose Maria Gatica was handed just his second loss in forty seven fights when Williams flattened him in the first. But, it seemed a combination of mob control, a tough career and competing at a higher weight were taking something out of Williams.

He was dropping a few here and there, some bad decisions, some not. On 25th May 1951 he ventured back down to lightweight, defending his title against Jimmy Carter. It was the first fight he had fought at the weight in nineteen fights. Was it a factor? Who knows. But on this night he came up short, being floored four times before being stopped in the fourteenth, losing his championship. That was to be his last fight as a lightweight. He returned, three months later, losing on points to Don Williams before being stopped in ten by then unbeaten Gil Turner. It was the only time he lost three in a row. He garnered a win stopping Johnny Cunningham in five before being stopped in five by Chuck Davey. There were rumours this fight was fought under “suspicious circumstances”, Williams himself claims he threw the fight, but reports claim Williams was taking too many when the fight was stopped. Nevertheless, it was clear to all that he was no longer the fighter of old. He fought his final twelve fights in good company, beating Claude Hammond and Vic Cardell along the way but losing to Carmen Basilo and up and comers like Georgie Johnson and Jed Black. He finished his career however, with two fights against old rival Beau Jack, drawing the first before stopping Jack in eight, finishing with not only a win, but also in the place where it all began, his hometown of Georgia. He finished with a record of 127-24-4 with 61 knockout’s. A fitting end for this once great champion.

Boxing on TV was in its infancy at the tail end of Williams career, a real shame as the man with the smooth style and knockout punch would have been a mainstay ten years earlier. That was Williams unfortunate dilemma, always ahead of his time. Fifty years later he would have been a multi-weight champion and millionaire. As it was, he finished up with hardly anything, thanks to Palermo who spent his purses as soon as Williams earned them. In 1960, Williams testified before a U.S. Senate subcommittee that was looking into the link between organised crime and boxing. He confirmed he was offered money to throw fights against Kid Gavilan, Freddie Dawson, Jimmy Carter and Juste Fontaine, refusing all. He did concede though that he wished he HAD taken the offers of $100,000 and $50,000 against Gavilan and Carter respectively, as he lost both anyway.

He was inducted into The Ring Magazine Hall of Fame in 1978, the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1983 and the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990. The Associated Press named him the fourth greatest lightweight of the 20th Century in 1999, whilst The Ring Magazine voted him the fifth greatest lightweight in history in 2001 and the 78th greatest puncher of all time in 2003.

All of his inductions not only immortalised his abilities as a fighter but also his self respect and integrity as a man. That, above all, counts for more than anything.

“He could have played piano with boxing gloves on”, said a ringside reporter as quoted in Bert Sugar’s Boxing’s Greatest Fighters.

“Ike was more than a world class fighter to me. Ike was a mythic. Ike was quite simply, with apologies to Benny Leonard, Henry Armstrong, Lew Jenkins, Beau Jack, Jimmy Carter, Bob Montgomery and even Roberto Duran, the best lightweight fighter who ever lived”. Bill Kelly: The History of the Sweet Science.