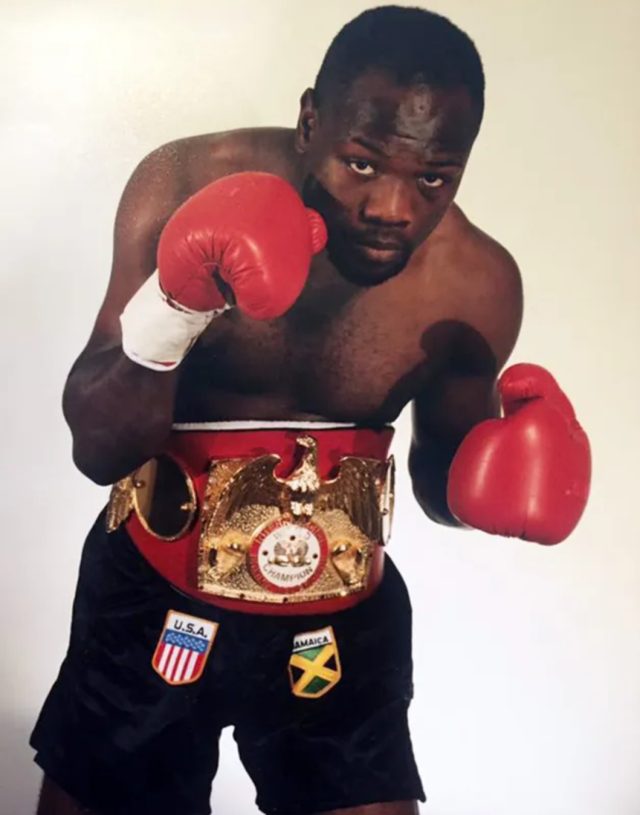

When Simon Brown speaks his voice belies the hardened warrior that lurks deep inside. A tinge of a light Jamaican accent is heard and images of him landing devastating left hooks couldn’t be further from the back of one’s mind. But for a period in the late eighties and early nineties, Brown was on the pound for pound lists, a fierce puncher who ruled the welterweight division, his reputation such that getting fellow elite fighters to share the ring with him would become virtually impossible as they preferred to look in an alternative direction.

Born 15 August 1963 in Clarendon, Jamaica, Brown was the fourth of six children. His mother and father earned their living growing yams, bananas and sugar cane. The children were all given their own spot to plant and Brown is of the opinion that this taught him patience, the patience of the seasons and how long things took to grow. He would be reminded of this patience when problems raised their head later in his career. After spending his formative years here, his family decided a move to Washington D.C. would provide more opportunities for them all. In 1974, his mother and father travelled to set things up as his grandparents took care of him and his siblings, with the children joining them two years later. However, fate may have played a part in this decision, as it was here that the young Simon first discovered the noble art.

His family never had a television in Jamaica but upon moving to the States this changed. And the world of boxing opened up to Brown when he was able to view the likes of Sugar Ray Leonard and Michael and Leon Spinks at the 1976 Olympics. It changed his life forever. He was hooked.

First Impressions

Pepe Correa ran the Latin Connection boxing club and had built the makeshift gym in a corner of the basement at the Calvary Methodist Church, fashioned with hemp rope, exposed pipes and crumbling brick. The bags were held together with masking tape and sometimes the ring would collapse, sending both boxers tumbling and becoming tangled in the fraying ropes. The Ritz it wasn’t. One day a 14 year old Brown walked in with a friend named “Poochy”. He sat watching the boxers go through their routine before asking if he could try. But he didn’t take to it straight away.

The sessions were three hours long and Brown discovered that he didn’t particularly like getting hit. When it was time to spar, he shied away, even going as far as to wear a bandage around his knee to feign an injury. But the technical side of the sport had fascinated him. He would call Correa late at night asking to show him how to throw a certain punch. Then one day the bandage came off.

“The real Simon Brown emerged” recalled Correa, “So I took him in to the ring. One day he caught my attention with a couple of left hooks. He was 132 lbs and he stung me. That’s when I knew he’d be somebody”.

Two years later, Brown had become so smooth that he had been given the same nickname as former welterweight champion Jose Napoles, “Mantequella”, translated from Spanish as ‘butter’. High praise indeed. It was also around this time that he would strike up a lifelong friendship with another boxer who would play an integral role, both personally and professionally, in his life; Maurice Blocker.

The pair became inseparable, meeting outside the gym after school at around 5pm. They were the most regular of all the kids, following Correa’s rules, “No cursing, no fighting outside of the ring”, and listening to his philosophy of life. But they rarely sparred in those days as Correa was unwillingly to put pressure on their friendship. That would be tested much later.

Lesson From A Legend

Brown had just sixteen amateur bouts, and as he prepared to make his professional debut, a surprise guest made an appearance at the Colombia gym in Northwest Washington D.C. Hitting the heavy bag, Brown noticed that everyone in the gym appeared to stop what they were doing. He turned to see that guest was none other than “Sugar” Ray Leonard. “I lit up” said Brown, “There he was. Wow! To see him there, it was unbelievable”.

He returned to hitting the bag when all of a sudden Leonard was beside him. “You’re throwing the hook too wide” he said “Throw it this way”. Leonard then demonstrated, throwing several short left hooks in the air. “See, real snappy, real short”. Brown absorbed the advice, firing a series of hooks on the bag. “That’s it, now you’ve got it” acknowledged Leonard, “Keep them short, snappy”. The lesson was brief but the impact was everlasting. “Ray was my idol” Brown said, “I wanted to be like him so much”.

He made his leap in to the professional world on 16 February 1982. But it wasn’t meant to originally be his introduction. Blocker was scheduled to make his debut that day and Brown went to support his friend. But at the weigh-in it transpired that a fighter named Ricky Williams was scheduled to appear but his opponent had been a no-show. Correa put Brown’s name forward and he obliged, winning a points decision over four.

He reeled off a further 16 wins, 13 inside schedule, as his ring education caught momentum. In early 1984 though, that education was taken to unprecedented heights when he was brought in to help Leonard prepare for his comeback fight against Kevin Howard. Six weeks of sparring three to four rounds, five days a week, elevated both his skill set and belief.

“No one could do anything to me after that”, Brown remembered, “After I stepped into the ring with him, I knew I would never fear another man again. What could anyone do to me that he hadn’t?”.

Back in action, he won his next four before challenging for his first title, the USBA welterweight title, held by the vastly more experienced Marlon Starling. Starling (34-3, 20 KO’s) had shared the ring with some of the best in the division, with wins over Floyd Mayweather Sr (twice), Tommy Ayers, Lupe Aquino and Kevin Howard. He had also twice lost close decisions to WBA & IBF champion Donald Curry. He would go on to become a two-time champion but for now, he was a test that many could not pass.

The First Defeat

On 22 November 1985, Brown found out just what it would take to earn a seat at the top table of the 147 lb division as he surrendered his unbeaten record to ‘The Magic Man”. The relaxed, smooth, low-left hand style that had proved so effective against lesser opposition was dissected this night against one of boxing’s finest ring generals. Boxing behind his high guard, Starling countered Brown’s jab continually throughout with the overhand right, pushing him back, and generally outworking the young prospect. Tellingly, Brown’s best work came when up close, planting his feet and ripping short hooks, a blueprint that was being laid for his future. After twelve rounds a split decision, that should have been unanimous, was awarded to Starling. For Brown it was time to reflect and rebuild.

He returned to action four months later with a seventh round stoppage of fringe contender Kevin Howard. But it was his next opponent that would help raise his profile to a higher level.

Canada’s Shawn O’Sullivan was a decorated amateur and had won silver at the 1984 Olympics, with many believing that he was robbed in the final against Frank Tate. Unbeaten in eleven fights, eight inside the distance, O’Sullivan was being fast-tracked up the rankings, managed and advised by none other than “Sugar” Ray Leonard. Brown was selected as the opponent to springboard him in to the top ten.

Travelling to Toronto, Canada on 8 June 1986, Brown demonstrated that the step O’Sullivan was attempting to make was more of a chasm. As O’Sullivan advanced, Brown, now defensively tighter than against Starling, tagged his upright opponent with right hands and used his shoulder and subtle movement to avoid being caught cleanly. On the occasions he was, he would blast back with sharp counters. By the third, it was obvious that O’Sullivan was in over his head. Brown blasted him throughout until a big left hook right hand combination sent him reeling in to a corner. A couple of heavy follow up shots forced the referee to intervene. Brown was now ready to prove he was a major player.

Lost Momentum

In the aftermath of victory, Correa called out the names of reigning champion Donald Curry and Leonard as prospective opponents. Leonard had been highly impressed with Brown. “I think he has power and speed, the ingredients to be a champion”, he said. “He changes style during a fight; sometimes he’s the fighter, then the boxer”.

However, behind the scenes Brown’s relationship with Correa had been unravelling. Correa had a falling out with the promoter he had found for Brown, Don Elbaum. As a result of this, Elbaum sued the pair for breach of contract. An out of court settlement was reached, but Brown was fuming for having to pay a percentage to Elbaum for something that he had been caught up in the middle of. “I didn’t trust my career in his hands anymore”, Brown said of Correa.

He then made a huge decision to remain inactive until his contract with Correa expired. It was a huge blow and any publicity he had gained from his victory over O’Sullivan would be lost. But Brown stubbornly refused to fight.

He trained everyday, but financially, times were tough. As previous funds ran low, old “friends” from the streets started rolling by in their flash cars and cash on the hip, trying out their speil on Brown; “You’re not fighting, you’re only training? You’re crazy! You could make money dealing or running. You can make a thousand dollars a night dealing cocaine”.

“It was tempting”, he said, even telling his wife Lisa who told him “I love you, but if you go that way I won’t be with you”. But he had been raised by a deeply religious mother. “She knew what was out there”, Brown said “A lot of my friends were dead or in jail. I’d never even been arrested. It wasn’t for me. I’d rather starve”.

Their respective families helped them with extras they needed until Elbaum came to see him with business partner Allen Baboian. Baboian instantly took to Brown whom he saw as a decent family man. Knowing of his struggles he wrote Brown a cheque for $5000. “You don’t have to sign with me for this”, Baboian reassured him, “If you decide you want to sign with someone else, fine. Life goes on. Just pay some of your bills. I want to make sure your mind is clear”.

It wasn’t just clear, it was made up. Brown wanted Baboian as his new manager. “He took a chance on me when I didn’t have a dime”, acknowledged Brown.

Kick-start

After fifteen months out, Brown returned on 25 September 1987 stopping one Dexter Smith in six rounds to shake off some ring rust. The following month welterweight champion Lloyd Honeyghan lost his WBC title to Jorge Vaca in a big upset. But as his IBF title wasn’t up for grabs, the title was declared vacant. The door was now wide open for Brown to face top contender Tyrone Trice to find a successor.

Detroit’s Trice was a sharp and heavy handed puncher. With twenty eight wins against just one reverse, he had halted twenty three of his opponents. It would be his first title opportunity too.

Champion..In A War

The pair met at the Palais des Sports in Berck-sur Mer, France on 23 April 1988. And what a fight they produced. Trice started the faster as Brown, fighting more flat-footed and aggressive, appeared a little off pace and rusty. Trice was anything but as he caught Brown with stiff rights. In round two, Brown got a complete demonstration of Trice’s power when his legs were buckled by a left hook. Struggling to remain upright, Brown staggered in to the ropes where a follow up right sent him crashing to the canvas. It was the first time he had been knocked down and he was in trouble. Surviving the round, he now knew the size of task he had to overcome.

Trice took the next two rounds as Brown started to warm in to battle. From the fifth round on, Brown started to find his rhythm, his jab setting up shots to Trice lean torso. Trice early assault had taken a huge amount out of him as he now became the pursued.

Brown almost dropped Trice in round ten when a right had Trice buckling like a drunk uncle at a wedding. Gamely he survived that, and also the eleventh, as Brown searched for the finisher. And in round twelve it looked like he found it. A short left hook sent Trice down by the ropes. Almost on instinct he rose but it wasn’t long before a second knockdown followed. He rose once again, but was driven face first in to the canvas by a right hand. It looked all over but, astonishingly, Trice peeled himself off of the floor as the the bell rang to save him. Brown had flung himself on to the canvas in celebration before being told the fight was still on.

There was no doubting that the fight should have ended there but Trice was allowed to continue. Clinging on for dear life and moving, Brown found his slippery target difficult to catch with a clean shot. Amazingly, Trice came out for the fourteenth letting his hands go. But it was one last fling of the dice. A grazing right from Brown sent him down on his front. Arising, he was in serious trouble and Brown went in for the finish, pummelling Trice until a left hook nearly separated his head from his shoulders. Referee Steve Smoger finally stopped the beating as Brown became the new IBF champion.

He became an active champ, defending his title twice before the end of the year. First up was a return to the country of his birth, Jamaica, against former WBC titleist Jorge Vaca. Brown was in devastating form, blasting Vaca to the canvas five times before it was mercifully stopped in round three. Then it was on to Switzerland where he outpointed the tough Mauro Martelli.

1989 saw him rack up a further four defences, beginning with a three round demolition of Jorge Maysonet in Budapest. Mandatory challenger Al Long was knocked out in seven, whilst Bobby Joe Young was stopped in two. He rounded off the year outpointing Luis Santana, establishing himself as one of the best fighters in the sport, with his style gradually morphing in to a stalking puncher with a wrecking ball left hook.

But frustration was kicking in. Many now started to recognise him as the best welterweight in the world. But proving that was becoming the problem. As talented as he was, his profile was low, meaning rival champs Marlon Starling (WBC) and Mark Breland (WBA) were reluctant to face him. He had come a long way since his sole loss to Starling and many felt he would reverse that result if the met again. Indeed, Starling had demanded $1mlllion to face Brown but had then accepted a lower payday to step up TWO divisions to meet IBF middleweight champion Michael Nunn.

There were also rumours that Julio Cesar Chavez was on the verge of moving up to 147. “Fighting Chavez would be a good challenge”, said Brown. “I’m not making a million dollars a fight, but I’m doing it the right way. I’m keeping busy. I’m a champion and I can’t waste it. I’ll make a million dollars some day. By god, I’m making it!!”.

His next defence was a rematch with Trice, this time at home in Washington. On 1 April 1990 at the DC Armory, the pair put on another entertaining fight, although less enthralling than their previous one. Brown had grown in to his role as champion and it showed from the start.

Trice opted to try to keep things at length this time, and counter Brown on the way in. But Brown’s pressure and intensity forced Trice to work and defend harder than he had anticipated. Landing the occasional hard shot, Trice was coming off second best as Brown slammed home hooks to the head and body, remembering how hard this man had made it for him last time. Brown broke through in round eight when a big left hook sent Trice stumbling to backwards to the canvas. He survived the round, and the ninth, but Brown closed the show in round ten when a barrage of punches drove Trice limply to the ropes, forcing the referee’s intervention.

Unsettlement within his camp had seen Brown change trainers for a few fights, dispensing with Correa to briefly hook up with Teddy Atlas before moving on to former world champion Emile Griffith. Now he wanted a big fight to showcase his talent and bank balance. But the only fighter prepared to meet him was also his best friend: WBC champion Maurice Blocker.

Blocker (32-1, 18 KO’s) had outpointed Starling to take his title after suffering his only loss three years previous in his first title effort against Lloyd Honeyghan. Known for being more of a boxer than puncher, ‘The “Thin Man” not only possessed the skills to trouble Brown but also had intimate knowledge of his friend’s strengths and weaknesses. Both men knew it was the only way they could both make a decent payday. “Neither one of us are taking this personally”, said Blocker, “This is just a competitive sport”. But how would they handle putting their friendship aside to do battle for twelve rounds?

Unification…With A Tear

On 18 March 1991 at the Mirage Hotel, Las Vegas, Brown and Blocker put on one of the best welterweight fights since Leonard vs Hearns ten years previous. And as chief support to the main event of Mike Tyson vs Razor Ruddock, their battle was seen worldwide.

Brown came out throwing a wide left hook, missing but raising gasps from the crowd. However, the point was made; he meant business. He pressed forward, looking to land bombs. But Blocker drew on their ring time together, offsetting Brown with a snappy jab and well placed hooks and uppercuts. While it was obvious that Brown possessed the heavier artillery, Blocker’s activity banked the first two rounds.

Brown started the third more purposely, bringing a strong jab in to play. A high left hook sent Blocker stumbling in to the ropes, eliciting a roar from the crowd. He was intent on ending matters early but Blocker fiddled his way through the round. Round four saw the action pick up. Brown slammed home several big rights as Blocker stood in the pocket with him, outworking him with flurries. But Brown’s shots were having the bigger impact.

Rounds 5 & 6 continued the pattern, although Blocker showed a tremendous chin as he absorbed a vicious right uppercut. Going in to round seven it was still all up for grabs. Blocker’s strategy of letting two and three punches go before tying Brown and keeping him off balance, was being executed superbly as he took the next three rounds. Brown’s frustration was evident as he searched for that one fight ending punch.

And in the opening minute of round ten, the explosive power of Brown resurfaced. A right cross set up a huge left hook that buckled Blocker’s knees before he involuntarily fell backwards to the canvas. Bravely rising, both men now faced their worse moment; Brown now had to go in for the finish. Blocker did everything he could to try to ride out the storm, holding on when close and then trying to stay at distance. But Brown knew he had to bring this fight, the one neither truly wanted, to a conclusion. One final clean right hand sent a dazed Blocker staggering across the ring as referee Mills Lane stepped between them. It was a truly, bittersweet victory.

Brown briefly, reluctantly, raised his arms in celebration before rushing his way to tightly embrace his best friend. Business can be brutal, but he was now the WBC & IBF champion. Big fights would surely now come his way.

But he made sure his best friend’s career could also continue at the same level, relinquishing the IBF belt, knowing Blocker would fight Glenwood Brown for the vacant title. Blocker won, becoming champion again on points. Brown would now prepare to face a very tough challenge in the shape of number one contender James “Buddy” McGirt.

Beaten By Buddy…And The Scales

The plan was for Brown to get by McGirt and then land a big fight with Julio Cesar Chavez or move up to face Terry Norris. But McGirt was one of the most stylish and smoothest fighters in the sport.

A former IBF junior welterweight champion, McGirt (54-2-1, 43 KO’s) had been on a sixteen fight win streak since losing his title to Meldrick Taylor. He was a throwback fighter with slick counterpunching skills and had been waiting three years for another title opportunity.

They met on 29 November 1991, The Mirage in Las Vegas playing host. Brown was expected to overpower the smaller McGirt but unbeknownst to many, he was battling two opponents that night.

Brown had been struggling to stay at 147 lbs for a while now. But the preparation for this fight really brought home to him that his time in this division was over. He had hardly eaten in the week before the fight, going from over 170 lbs down to the welterweight limit. Even the night before the fight he had to lose 4 1/2 pounds. It was a huge amount to take off. And it would come at a price.

Facing McGirt at full strength would have been hard enough but Brown was facing a lost cause. He was outboxed from the get go, with McGirt dominant behind his jab and sharp combinations. Never able to get set due to McGirt’s tactics, Brown was reduced to following his opponent for round after round with limited success. And each round took that bit more out of him. In round ten, he walked on to a left hook that sent him tumbling face first to the canvas. Wearily rising, he survived the round. It was the cherry on the cake for McGirt as he continued his display, taking Brown’s crown with a one-sided unanimous decision.

Brown spent five days in hospital after, suffering the effects of dehydration. “I’m not fighting anymore at welterweight”, he said after, “I’ve been at this weight since 1979”.

Moving On Up

Brown parted ways with trainer Griffith, replacing him with Ritchie Giachetti on the recommendation of Don King who had been promoting Brown. But this pairing only lasted for Brown’s first two fights in ’92 at junior middleweight before he reunited with Adrian Davis, whom had been a part of his camp a while back. Davis wanted to take Brown back to his boxing more, feeling that he had become over-reliant on his power.

Three wins to start 1993 put Brown in line for a shot at division leader and WBC champion “Terrible” Terry Norris. Norris (36-3, 22 KO’s) was an explosive boxer-puncher who sat very high on many experts pound for pound list. Having effectively “retired” “Sugar” Ray Leonard and Donald Curry whilst making ten defences of his title, he had established himself as one of the hottest fighters in boxing.

But a grudge existed between the two. They were originally meant to have met the previous year on 26 September 1992. But just hours before the fight, Brown pulled out citing dizziness and feeling unwell. It was later confirmed to be an inner ear infection. Norris was more dismissive though, claiming that Brown was running scared. Rubbing his nose in it further, Norris then destroyed Blocker in just two rounds in February. Brown vowed to gain revenge for the pair of them.

Upset …And Revenge

Brown was well aware of the task in front of him, acknowledging that he had to treat this like it could very well be his last chance to become world champion. He spent a month in Mexico beforehand, acclimatising to the altitude. A big underdog, he had prepared diligently for this moment.

On 18 December at the Estadio Cuauhtemoc, Puebla, Brown came out cautiously behind his jab. But Norris had been on a path of destruction lately and he felt he could go through Brown, staying on top of him and ripping in tight, short punches. His power was evident, but Brown always had a sturdy beard. The same could not always be said of the defending champion.

As the end of the round approached, Brown stepped in with a heavy jab. The punch connected on the side of Norris jaw and it looked like someone had yanked a rug out from under his feet. He hit the canvas, flat on his back. As he arose, it was apparent his legs weren’t quite with him. The round ended before another punch could be thrown, but Brown had made his intentions clear; he was here for the title.

Norris started the second like nothing had happened, going straight on the attack. Brown took a few shots but also rode some off of his shoulder, showing the influence that Davis had made. And as the round wound down, he struck again. A thudding right hand high on Norris head took the strength from his legs again. Norris was in trouble as the bell ended the round.

But still Norris kept coming. He appeared refreshed after the rest and fired off more right hands. Brown started to connect more throughout the third. But once again, with five seconds to go, Brown caught Norris flush with a right left hook right combo that sent Norris legs splaying in all directions. As the bell sounded, he had to be helped back to his corner.

Entering round four, the scent of a huge upset lingered around the arena. Brown had dropped Norris and hurt him badly twice. But the resounding question was “Could he knock him out?”. Brown started in a southpaw stance, pushing Norris back as he gained momentum. Norris was still dazed and the writing was appearing on the wall. With just a minute gone in the round, Brown slammed over a big right hand, the punch hitting Norris between the neck and back of his head. He pitched forward, rolling on to his back as he was counted out. Brown was back on top of the world.

There was no chance of resting on his laurels when just six weeks later, he defended the title against hardened challenger Troy Waters. It was an industrious display from Brown, who took a majority decision over the Australian to retain his title.

Next was a return with Norris. Don King advertised the card as “Revenge: The Rematches” with four world titles on the line against former opponents. Despite his previous, convincing win, Brown was once again considered an underdog.

Ex-Champion

At the MGM Grand in Las Vegas on 7 May 1994, Brown surrendered the title back to Norris in a one-sided spectacle. Norris adapted his approach, this time using foot and hand speed to make himself an elusive target as he racked up the points. Brown was unable to pin down his rival and land punches like he had previously. He lost a wide, unanimous decision.

Afterwards, Brown offered no excuses. “He outmoved me and he outboxed me”, he admitted before adding, “He moved a lot, I expected that, but he just wouldn’t stand still at all”.

But Brown still presented dangerous opposition against the right style of fighter. And after two comeback wins, that right fighter appeared to have been found.

Vincent “The Ambassador” Pettway was the reigning IBF junior middleweight champion. He had won the title off of long reigning holder Gianfranco Rosi with a fourth round knockout, having drawn their first fight. His record of 37-4-1, 1 NC, also featured 30 wins via knockout, indicating the power he carried. But his defeats also exposed his vulnerability, with all four coming inside the distance. This also included suffering several knockdown’s too along the way. It was a combination on paper that appeared to not bode well against Brown.

THAT Knockout

They met on 29 April 1995 at the US Air Arena in Landover. Brown had come looking for the knockout. He pursued the champion who had adopted a box and move approach. It was a quiet opener until, with 30 seconds left on the clock, Pettway caught Brown with a sharp left hook. Brown responded with his own, thudding high on Pettway’s head. His legs disconnected from his legs as a further hook catapulted him to the canvas. He rose but was saved by the bell.

Pettway got back on his bike in the second as Brown looked to repeat his earlier success. Pettway’s strategy looked sound as the challenger struggled to connect.

The pattern continued through the first part of the third. Then with just over half of the round gone, Pettway caught Brown on the end of a right hand counter. Brown’s legs stiffened as he fell back to the canvas. The crowd went wild at the sudden turn of events. Brown sat in a squatting position as he listened to the referee’s count. The action resumed and Brown’s legs were buckled with another right. The bell rang to take him out of harm’s way.

But Pettway got back on his bike in round four, failing to press his advantage. Brown caught Pettway with some stiff shots, sending a message that he was still there. Things got wild in the fifth when a low blow led to Pettway being sent half way through the bottom rope, courtesy of a follow-up right from Brown. Pettway was fuming and retaliated instantly. Unfazed, Brown kept coming. But Pettway wasn’t letting it go and punches were exchanged after the bell as each respective corner voiced their anger. The crowd were loving it.

There are moments in boxing that will stay forever etched in your mind. And midway through round six became one of them. With his back to the ropes, Pettway launched a devastating left hook, the punch detonating on to Brown’s unguarded jaw. He fell back like a chopped down tree, flat on to the canvas, his eyes closed tight. Eerily, he continued to throw jabs, his left arm flicking out involuntarily. There he lay as he was counted out for the first time in his career.

Several months after, Brown recalled the knockout. “I was winning that fight until that split second”, he said, “I made a mistake and I paid for it…”. He continued. “I remember the punch. My hands had always been up where I could catch it. But not that time. There are always obstacles in life to overcome. This was one for me”.

His contract with King was over and he signed with promoter Bob Connelly and also re-signed with Elbaum to act as advisor.

Brown moved up to middleweight, chasing a championship in a third division. However, his first fight in five months didn’t go quite as planned. In with former WBA welterweight champion Aaron Davis, Brown boxed relatively well. But in a high quality bout, he just wasn’t busy enough, dropping a unanimous decision.

It was viewed as a minor setback, but it was also a signal that Brown was in the veteran stage of his career. And he was still considered a world class opponent and a “name”. So two wins later, he was offered the chance to capture a version of the 160 lb championship. Step forward WBO king Lonnie Bradley.

Bradley was unbeaten (24-0, 19 KO’s) and was searching for his breakout fight. Whilst Brown wasn’t the marquee name he desired, he was still a step up from his previous competition.

They met on 30 August 1996 at the Municipal Centre, Reading, Pennsylvania. And it once again, highlighted Brown’s trouble with movers. Whilst he remained competitive in the fight, the scorecards painted a different picture. Bradley’s jab and footwork were the key. They gave him the edge in nearly every round, and he retained on a wide, unanimous decision.

But Brown still had one more title chance in him. Two victories put him next in line to face the man regarded as the number one middleweight in the world; IBF champion Bernard “The Executioner” Hopkins.

Last Hurrah

Hopkins (33-2-1, 25 KO’s) was still in the early stages of what would turn out to be an astonishing Hall of Fame career. At this point, he was a more aggressive boxer-puncher, before his metamorphosis in to the wily technician that he became known for. Brown would be his seventh defence.

At the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City, on 31 January 1998, Brown saw the beginning of the end of his career. Hopkins was just too much of everything for him, breaking the proud warrior down, before sending him to the canvas at the start of round six with a short right uppercut. Bravely rising, Brown was overwhelmed by an onslaught of punches against the ropes, whilst still trying desperately to find that one last fight changing left hook. But he was taking too much. The referee stepped in, ending his final aspirations of becoming world champion again.

Brown wouldn’t see victory again, losing his final five fights against opponents he would have beaten in his prime.

His final record: 47 wins, 12 defeats, with 34 KO’s.

On 22 August 2021, he was inducted in to the Atlantic City Hall of Fame.

After retiring, Brown became a trainer, moving to Los Angeles to work alongside his former trainer and manager Correa in the “All American Heavyweight” program. But in 2013, he was ready to move back to Maryland.

“My wife Lisa and I were looking around, thinking Hagerstown is pretty good, a little more country, laid back, quiet”, he said, “so we decided to move here”.

In 2017, he opened up his own gym, The Simon Brown Boxing Academy. He works with all age groups, with the mission not just being about creating champions, but also changing lives.

“It’s a lovely sport and keeps a lot of guys out of trouble”, he explained. “Instead of running on the street, they can be here, doing something instead. I try to pull all the guys that I can in, and 90 percent of the guys, I don’t charge them anything. My dream for this is to keep a lot of young guys off the streets, to stay off drugs and alcohol and stop running the streets and carrying guns. If I can pull them into this gym, that’s my goal”.

Reflecting on his own career and his difficulty in getting the superfight he so deserved and craved, he said “They were all scared of me. They didn’t want to get hit by this left hook. They all ran away from me as much as possible”.

And despite his caring and thoughtful nature, a competitor still lurks deep inside. “My only regret looking back is, I wish I’d got those big, big money fights with Chavez and Breland”, he admitted, before the champion of old appeared one more time; “I’d have beaten them both”.